Not long ago we made a short Caribbean cruise aboard the Royal Caribbean Jewel of the Seas. Our trip took us along the western Caribbean and into some interesting ports along Central America. One stop that we found fascinating was Colon, Panama. This is the Caribbean entrance to the Panama Canal, and we had a chance to view the locks in operation.

Our original ship’s itinerary was supposed to take us through the locks for a day cruise around Gatun Lake, but schedules with the Canal authorities changed our plans, and we ended up making a land based visit instead. No loss for us since we were happy to spend time watching other ships go through the locks.

The Locks

Until the Panama Canal was constructed, ships that needed to transit from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean in the Americas needed to travel all the way down to the southern tip of South America. This route added significant time to a voyage, and at the time that construction first began in 1881, was a dangerous route to sail. Actually, it’s not all that easy in the 21st century since the southern tip of South America sees some of the most severe seas and weather in the world.

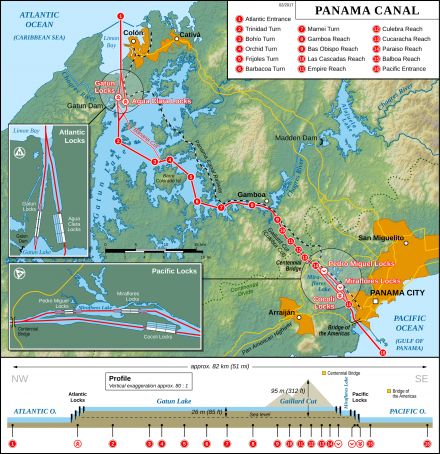

Much of the Panama Canal was created by building the Gatun Dam across the Chagres River. The new lake added 21 miles of waterway across the Isthmus of Panama. Illustration By Thomas Römer/OpenStreetMap data, CC BY-SA 2.0, Link

The lock system used at the Panama Canal has three steps to raise and lower ships the 85 feet needed to reach the level of Gatun Lake. Each lock is filled from the “uphill” side and therefore requires no pumps to fill each chamber with water. In fact, the only significant power needed to operate the locks is for the valves that open and close allowing water to flow, and the gates that open and close allowing ships to pass. The first two sets of locks were placed into service in 1914. They are 110 feet wide and at the time and could accommodate pretty much all ships. The first year saw around 1,000 vessels making the eight hour journey across Panama. By 2008, over 14,000 vessels passed through.

There’s a term called “Panamax” and “New Panamax.” These refer to specifications published by the Panama Canal Authority since 1914. They specify how wide, long, tall, deep, and so on a ship can be and still traverse the Panama Canal. The term Panamax referred to specifications necessary to enter the original locks, completed in 1914, and the term “New Panamax” of course refers to the specifications necessary to fit into the new locks. It’s probably fair to say that the designers of most of the world’s largest ships that are afloat today have seriously considered the specifications defined by the Panama Canal Authority.

A problem has been developing over the past few decades for the Panama canal because many cargo ships being built in the modern age are simply too big to fit through the older locks. The ships are either too wide, too long, or both, so the Panama Canal Authority began construction of a third lock system on 2007 that was 30% larger. Actually, the US started construction of new locks in the 1930s but suspended the work at the beginning of World War II. In 2016, a third lock was added to either side that was 180 feet wide, 1,400 feet long, and 60 feet deep. As large as these locks are, they can still only accommodate about 79% of all the ships in operation today.

We spent some time at the locks watching ships moving through, and it was a fascinating operation. As a ship is readied, it is moved into position, usually by a tug boat, then attached to vehicles on train tracks called Mules. These are heavy vehicles on train racks, resembling small locomotives. There were usually four of these mules on each ship. There was a surprising amount of scratching and scraping between the ships and the sides of the lock, but often times there was no more than six inches to a foot clearance on either side. What really surprised us was that the mules, as small as they were, could wrangle these ships through the locks.

Lake Gatun

There were many boat tours of Gatun Lake which was a pleasant way to spend a couple of hours. Photo by Donald Fink.

Part of our ship’s tour included a leisurely boat ride around Lake Gatun, the lake that comes immediately after the locks on the Atlantic side. We spent about an hour out on the boat, mostly taking in the wildlife, from the occasional Howler Monkeys in the trees, to the Caiman, scrambling to get out of the way of the boat. There were several different species of birds fishing the waters as well as making their homes in the overhanging tree.

Gatun Lake is artificial. The Gatun Dam was constructed between 1907 and 1913 as part of the Panama Canal project, filling in the Cagres Valley with nearly 183 billion cubic feet of water. The lake supplies the water necessary to operate the Gatun Locks, but also serves as nearly 21 miles of the 48 mile distance ships must travel across the Isthmus of Panama. At the time that Gatun Dam was built, it was the largest dam in the world.

Aside from providing much of the water to operate the Panama Canal, and making a 21 mile route across Panama, Lake Gatun is home to a thriving outdoor tourist industry. It’s also home to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, which is locate on Barro Colorado Island. Along with several surrounding small peninsulas, Barro Colorado Island forms the Barro Colorado Nature Monument, administered by the Smithsonian since the 1940s. This area has been among the most closely studied tropical forest areas since the completion of the Canal. Much of what we’ve learned about the rain forests on our planet has come from this island.

Magnificent Frigatebird

There’s a bird we’ve seen over the years that always catches our eye, called the Magnificent Frigatebird (Fregata magnificens). It’s like one of those memories that burns into your mind, like hearing the sound of the boats on Bay Lake at Walt Disney World, or the train whistle at the Magic Kingdom. For us, we’re in our “happy place” when we hear those sounds. Seeing the Frigatebird is much the same. We see them when we’re on a cruise, so we associate them with our cruise ship happy place.

Frigatebirds are interesting creatures. First, they’re large birds. They can have a wing span of up to 88 inches (224cm). They look similar to a Swallow Tailed Kite, but the kite is of course a much smaller raptor that lives primarily over land. The frigatebird is seen over water, feeding as it skims the surface. They take fish from the surface, and flying fish when they find them. They’ll also harass another bird until it regurgitates, then catch that food before it reaches the water. Yum! Their usual range is the southern US coastline, Mexico, the northern and eastern coastline of South America. They’re also spotted off the coast of Africa on Cape Verde. Christopher Columbus commented about seeing them at Cape Verde his journal during his first crossing to the Americas.

We were once under the impression that if a frigatebird happened to land on the water, they couldn’t regain flight, but a little research now tells us that they can. It’s just that a water landing by a frigatebird is extremely rare, and probably not intentional. They can actually fly for long periods of time without landing, sometimes several days and nights.

We enjoyed our trip to the Gatun Locks of the Panama Canal. This goes down for us as one of those places that we were glad to visit, but would probably never actually fly in and make a two-week vacation out of it. We were happy to do it on a cruise, where we were in and out, with just the quick overview. The locks were fascinating and well worth the visit, but truthfully, even a geek like Don can stand there only so long and watch water go up, then go down.

Here are a few of the images we brought back from our day in Colon: