One of our favorite pass times when traveling in the American southwest is visiting the various cliff dwelling houses. Places like Mesa Verde come immediately to mind, but the area is scattered with many more out of the way places that can really make an adventure to the southwest something special.

One place that we’ve enjoyed visiting in the past is Chaco Canyon. Formally, it’s known as the “Chaco Culture National Historical Park.” It’s located in the northwestern corner of New Mexico. We could say it’s near the town of Cuba, but the truth is, it’s more accurate to say that Cuba is one of the nearest towns. It would seem to be not quite true to claim that Chaco Canyon is near anything at all, and that for us is the point.

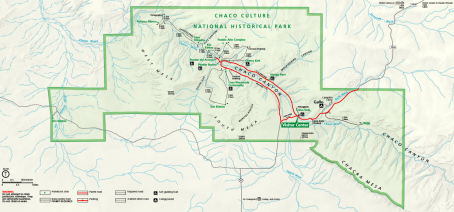

How to Get There

To get there, you can travel from the Albuquerque area along New Mexico State Highway 550 most of the way. It’s a four lane freeway running diagonally through the state between Albuquerque and Farmington. If you’re coming from Colorado, you can go through Durango, down to Farmington, and on to Chaco Canyon. There are thirteen miles of dirt roads to drive before getting to Chaco Canyon, and the last four miles are considered by the park service to be very rough.

Here is a link to the official park service directions for getting there. We can verify that the roads are indeed rough. While they’re passable by just about any vehicle, they had a lot of wash boarding which makes for a rough ride that’s hard on your car. During really wet weather, we might be a little concerned about using a two wheel drive vehicle, and big touring bikes (Harleys, Gold Wings, and so on) are simply out of the question.

Accommodations

There are no hotels near Chaco Canyon and it’s dirt road access makes it difficult-although not impossible-to do a simple day visit. There is one campground in the park, near the visitor’s center, called the Gallo Campground. It has 49 regular campsites and 2 group sites that can accommodate between 10 and 30 people. The regular sites are most appropriate for tent camping, and most of them have a tent pad. RVs up to 35 feet can fit in the campground, but there’s no water at the sites, no power, and no sewer, although there is a dump station in the campground.

Generators are allowed between 8:00 am and 8:00 pm, but only for one hour at a time. Visiting this park in an RV might be a good reason to upgrade your rig with solar panels.

Why Visit Chaco Canyon?

First, there’s the solitude. With no running water, no power, no cell phone connection, this experience has always been what we consider an essential experience when visiting the southwest. The absolute silence is very satisfying. There are many places in the American southwest where you can experience this kind of silence, but it seems more intense here in Chaco Canyon, assuming that “silence” can be considered “intense.”

Chaco Canyon is listed as an International dark sky Park with the IDA Dark Sky Association. To most of us, this simply means that it’s got really, really dark skies. Enough so that you can stand outside at night and easily see the Milky Way. For those of you who occasionally like to view the night sky, this place is so dark that you can look directly at the Pleiades Constellation and see it, without using offset vision.

We were there one night when one of the group sites was occupied by the Albuquerque Astronomical Society; a group of friendly people willing to share their views from their amazing telescopes. You might imagine that a group of amateur astronomers from Albuquerque are used to pretty good viewing and they were raving about the conditions at Chaco Canyon.

What Else is Here?

Of course, the point of visiting Chaco Canyon is to view the ruins. The dark skies are great, and the solitude is even better but the point is that Chaco Canyon is considered to be the central cultural center of the Ancient Pueblo People. The city is thought to have been at its peak between AD 900 and 1150 and was home to the largest concentration of Ancient Pueblo Peoples in the American Southwest. It’s also believed that it was a major trade center because of the abnormally high number of storage areas found in the ruins and the existence of well-developed roads leading into the city. The notion that it was a cultural and religious center comes from the evidence that it seems to have a larger than normal number of ceremonial areas too, compared to the number of people who were thought to live here.

It’s possible that all sorts of activities centered around trade, culture, religion, and even art could have taken place here and spread its influence all throughout the Colorado Plateau.

Most of the ruins can be visited in a day. There is reasonably good road access to all the major ruins as well as hiking trails between them. There are also several ruins that are more remote and accessed only by walking, but the trails are open to the public and well marked.

The visitor’s center is staffed year round and is a starting place for your adventure here.

A Word About the Anasazi

You may notice that we keep calling the folks who lived here the Ancient Pueblo Peoples, and not Anasazi as they have been called in the past. The reason is somewhat complicated, but easy enough to understand. It seems that the word Anasazi is actually a Navajo word that means “Ancient enemy.” But it’s more than that. Without a literal translation, the word apparently has negative meanings that go beyond simply, “Ancient Enemy.”

It was first used back in the mid-nineteenth century by Navajo workers who were hired to go out and collect pot shards and other artifacts lying about ancient ruins. This is of course, back when we used to do that sort of thing to our historical sites. At the time, there wasn’t a word to describe the people, so the Navajo term caught on. It Turns out though, that there’s no particular reason to think that the Anasazi were enemies of the Navajo, any more than they were anyone else’s “enemy.” the problem is that there is no spoken or written history left over from the Anasazi, so we actually have no idea what they called themselves. It might be that they didn’t call themselves anything since evidence suggests that they were made up of many different cultures.

Still, we have the need to catalog and characterize, so we used the name Anasazi until recently. It turns out that there are people in the southwest that consider themselves ancestors of the Ancient ones, and they aren’t fond of the term Anasazi, because of its negative connotations in the Navajo language, and perhaps also because it’s a Navajo word and the Navajo aren’t regarded as descendant from these ancient people. For that reason, experts in the field have started using the term Ancient Pueblo Peoples out of courtesy to the present day Puebloans, and, quite truthfully, because we have no idea what they originally called themselves.

Visited Chaco canyon, and can say without a doubt, that it was the most unforgiving road I have every driven. Top speed never exceeded 5-15mph for fear of destroying our 4×4 Pickup. Horrible.

To be as interesting as it was, and promoted as it is, you would think the road would be a bit more maintained… I could see no evidence of ANY upkeep on the road. Would love to stay longer but could not imagine driving it again when we were to leave. Extremely interesting, but will NEVER make the drive again…. Disappointing to say the least.

When we were there last, the road was in pretty good shape. In fact, the grader was actively working the road when we came in. Other times, we found the road just as you describe here. And of course, you never know which one it will be until you get there.

One of the things I like best about the roads into Chaco Canyon is their condition. I’ve driven in from both the south and north numerous times. The challenges of the roads keep out people who shouldn’t be there anyway.